One night my freshman year in college, I was deep into a late night cafeteria debate with two fellow peers – the kind I had once imaged university dinners would be filled with, only to realize they more often consisted of comparing hangovers and midterm notes.

But that spring night, over a plate of fresh-out-of-the-oven chocolate chip cookies in the Segundo DC at UC Davis, one of my floormates and I were trying to explain to someone from our building what it was like to grow up as a first-generation American (my parents had emigrated from Greece, his from Iran).

Our friend said he didn’t believe in the kindred connection we said we felt to people from our culture, whose only similarity to us was that our parents had been born in the same country. We tried to explain to him the shared experiences – the different holidays, the weird customs, growing up in a household that didn’t just speak English at home – but he didn’t get it. He said it was all merely geography. “Why should it matter where people are born?” he asked. He said he believed, at the end of the day, that we were all “the same” – that that world was “colorless.”

Turn on broadcast television today and you see diversity everywhere. Empire rules Fox (not to mention every other show on the Big Three). ABC’s #ShondaThursdays are filled with strong, powerful African American woman on Scandal and How To Get Away With Murder, not to mention the wonderfully multi-ethnic/racial cast on Grey’s Anatomy. Even CW has become a critic’s darling with Jane the Virgin.

All of these shows discuss racial, ethnic, and religious differences. But there were no recent shows on television (at least that I was aware of) that were distinctly about the minority experience. That is, of course, until Fresh off the Boat and Black-ish came along.

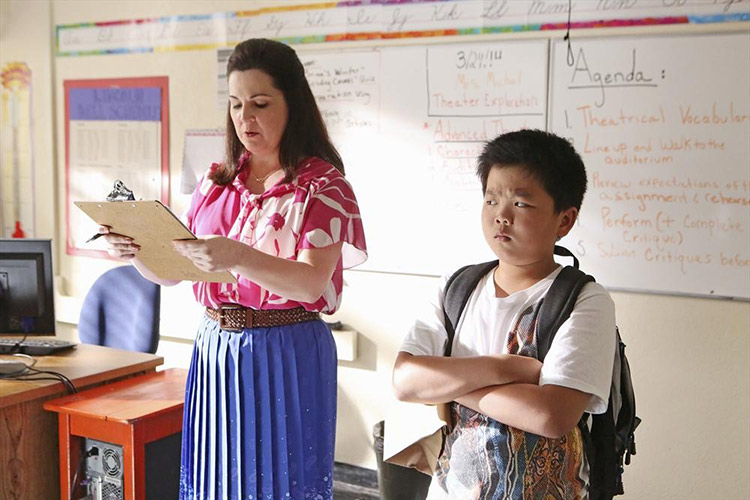

Fresh off the Boat, based on chef Eddie Huang’s memoir of the same name, follows a young Eddie and his Taiwanese family in their move from Washington, D.C. to a predominantly white Orlando suburb. It is the first network television show to feature Asian Americans as the protagonists since Margaret Cho’s quickly cancelled All American Girl in 1994.

The first episodes focus heavily on the family’s difficulty assimilating into their new neighborhood. Eddie’s teacher can’t pronounce his name and he gets kicked out of the “cool” table because he eats homemade noodles instead of Lunchables. His mother Jessica (the terrific Constance Wu) has an equally hard time fitting in, feeling out of place in the cold supermarket aisles, where she’s not allowed to bargain, or hanging out with the Rollerblading Housewives, who refuse to eat her “stinky tofu” dish during their potluck lunches.

In the first-half of Black-ish’s fifteen or so episodes, it’s the opposite problem. Patriarch Andre ‘Dre’ Johnson believes his kids have settled into their affluent white suburb too well. The first couple of episodes revolve around something Dre tells his family in the pilot: “I’m still going to need my family to be black – not black-ish, but black.” Dre is pissed when his son wants to try out for field hockey instead of basketball. Dre is pissed that his son doesn’t have any black friends. Dre is pissed his son wants a bar mitzvah, and that his friends call him Andy. Dre is pissed his younger children identify the only fellow black child in their class by the kind of clothes she wears instead of the color of her skin. When his wife Rainbow says, “isn’t that beautiful, that they see the world as colorless” he responds with a resounding “no.”

I may be neither Taiwanese or African American, but I found myself relating to so many of the storylines in both shows. That scene where Eddie brings noodles to the table? I am still scarred with the memory of spending a lunch period in the bathroom, frantically washing the fish stink out of my Animaniacs lunchbox before anyone in my class realized “that weird smell” had been coming from me. And the frustration Eddie feels when his teacher tries to pronounce his Taiwanese-given name? That was me during every first day of the school year and every time a substitute teacher came in, so fed up that I would yell “here” right before they could call me a variation of “Anita Konstantitties?”

Long before My Big Fat Greek Wedding made the motherland cool and the debt crisis made it a running late night punch line, I just wanted to be like everyone else. I wanted strawberry blonde hair like my idols (Mary Kate and Ashley), the ability to stay at sleepovers as long as I wanted (damn you Saturday Greek school), and to be one of the five girls named Jennifer in my class.

When I first started watching Black-ish in its early episodes, which were hyperfocused on Andre and his fear that his kids were forgetting their roots, I was reminded of the own identity crisis I had as a kid. Was I supposed to be more Greek or American? When I visited Greece over the summer there were days when I wouldn’t speak at all, too embarrassed by my accent to speak Greek. Back in America I bought star-spangled flip-flops and watched Nick at Nite, trying to figure out how to blend in despite my caterpillar eyebrows and five-syllable last name.

When the real Eddie Huang saw how his childhood story was being broadcast-ized for an American audience, he was angry. He wrote in a scathing Vulture article that he began to “regret ever selling the book,” as he was forced to watch “specific moments of his life” become filtered into a “universal, ambiguous, corn starch story about Asian Americans.” He argued that the network’s approach to displaying Asian Americans in protagonist roles on television was to say “we’re all the same.”

But that’s the thing. As both Fresh off the Boat and Black-ish have continued to get the chance to grow and develop, they have become classic family sitcoms. They still tackle specific and important storylines – including when Eddie is called “chink” in the cafeteria, and when Rainbow becomes angered by microaggressions on the baseball field – but they also get into the same hijinks, whether it’s a bad Valentine’s Day date or a prank war, that has defined their genre since the 1950s, when the only families on our television screens were white. At the end of the day, everyone’s story is still the same.

Fresh off the Boat and Black-ish so wonderfully capture the universal feeling of the outsider – and not one solely defined by race or ethnicity. One of the first things Eddie says in the pilot is that he is the black sheep of his family. He listens to hip hop and begs for Air Jordans and video games while his two younger brothers study hard, have perfect attendance records, and find girlfriends with ease. When Dre succeeds in helping his son make a fellow black friend, he realizes what they’ve bonded over is a shared love for The Hobbit – not a shared color of skin. “The struggle comes in different forms,” Dre realizes as he gives “the nod” to a fellow black man, while his son nods to a fellow nerd.

In his essay, Huang says the “universal demographic doesn’t exist” but then later acknowledges that “the feeling of being different is universal because difference makes us universally human.” It’s not another Asian mother Jessica finally bonds with in Florida, it’s a sweet trophy wife named Honey who shares her love for Stephen King films and enjoys her stinky tofu. Eddie makes friends with kids who also worship Shaq and know what it’s like to get picked on riding the bus, all of them closing their eyes in camaraderie as they pretend to nap and avoid the bullies.

What I failed to realize that night in the cafeteria is that shared experiences did not necessarily have to mean shared culture. I may have had to spend eight years in Greek school, but one of my best friends had to do 10 years of training in Bharatanatyam classical dance. And how many of us have felt insecure about the food we used to bring in our lunchboxes – whether it be fish or “moose kaka” or just a soggy peanut butter and jelly sandwich with the crusts left on?

Basically, it’s the human experience of being different that makes us all the same. And that’s finally being reflected on our televisions today.

Liked this. Sending this over to a friend of mine who has told me great stories of moving to NYC from Greece.

Thx,

Thelma