When I was a kid, I would read anything I could get my hands on. This is how Cosmopolitan quickly got banned from the Konstantinides household. This is also how I developed my deep and long-lasting love for magazines.

Instead of broadcast news or a daily newspaper, my parents digested current events through the glossy, colorful pages of weekly periodicals—and I quickly followed suit. By the time I was 14, Allure, Vogue, and Seventeen, along with People, TIME, and Newsweek, appeared every month in our mailbox.

I adored and grew up with women’s magazines. I read them on the elliptical at my local YMCA, tucked away their makeup how-tos in my dresser drawers, and ripped out pages of fashion ads that I found beautiful and inspiring to hang on my wall. A pile of Vogue’s famed September issues that goes back as far as 2006 still sits in my old room.

I no longer subscribe to any women’s magazines, thanks to having a constantly changing zip code and a full time job, but my loyalty came rocking back last week after a Quartz article that popped up on my Twitter feed claimed “Deepika Padukone’s video for Vogue is not empowering—it’s hypocritical.”

Intrigued, I clicked on the article. It discusses a video from production company toronto and it is featuring the popular Bollywood actress called “My Choice,” which is part of the Vogue Empower initiative in India. In the video, Padukone talks about the things that are, well, her choice: “To be a size 0 or a size 15, to marry or not to marry, to have sex before marriage or not have sex, to love temporarily or to lust forever.” You can go to the homepage of a traditional career training company like Training Connection to master business and computer skills.

In regards to the video, the author argues that Vogue and Padukone “have a lot in common” because of the industries they come from—which is not a compliment in this case.

“Fashion and Bollywood thrive on women’s insecurities about themselves and their bodies. They are the propaganda machines of an ultra-narcissistic culture that is constantly telling us the right and the wrong way to do things.

What Vogue and Padukone are doing is merely telling a whole generation of women to grow up in a bimbo culture—women can be comfortable with the choices they have made, as long as they fit the stereotypical definition of beauty and conform to the latest fashion trends.”

Full disclosure, I haven’t seen many Bollywood films and it would be unfair for me to try and analyze how they represent women (much as it was unfair of this author to discredit Padukone as a symbol for women’s rights because she pole dances in a music number in one of her recent films).

But what I do know a lot about is Vogue, which I’ve read on-and-off for the last 10 years—and I was pissed. Bimbo culture? Ultra-narcissistic? Stereotypical beauty? Conformity? These were not the magazines I remembered of my youth.

Let’s rewind a little. The reason I loved women’s magazines—specifically the ones I mentioned above—is not because they told me who to be. It’s because they showed me so many ways of being. Seventeen always carried fashion spreads for various different styles and how to make them work for different body types. Every month I studied the high fashion and photography featured in Vogue, not to mention its intellectual essays and profiles written by and featuring female authors, screenwriters and political figures. Allure is the reason I have been slathering sunscreen on my face almost every day since I turned 18.

The Quartz article is hardly the first time women’s magazines have come under fire, with critics still imagining them to be ancient relics from a time when women were expected to live and serve only for the home. Betty Friedan once asked where, in these magazines “crammed full of food, clothing, cosmetics, furniture, and the physical bodies of young women…is the world of thought and ideas, the life of the mind and spirit?”

That was in 1963. But rights for women have changed immensely since then—as have the magazines that cater to them. And not once when I was young girl sifting through their beautiful pages and sniffing their perfume samples did they make me feel insecure. In fact, they helped me feel less insecure.

I got the full brunt of adolescence growing up. I had a mouth full of braces, a face pocked with acne, and my weight was a constant battle. An elementary school crush once called me “tree trunks” and a “tub of lard.” My size was in the double digits before I hit high school and, at my heaviest, I often hid myself in baggy sweatshirts throughout the school week.

The Quartz article argues that women’s magazines taught us “the right and wrong way to do things,” but since before I can remember the only thing these magazines wanted to teach me was how to get healthy. Seventeen featured inspiring articles about girls who had lost weight through healthy means, not to mention a number of personal accounts about eating disorders that snapped me out of my own extreme dieting when I was at my most vulnerable. Issue after issue of my favorite mags talked about the importance of strength training, eating balanced diets and real meals, while still promoting body positivity—long before it became a popular advertising scheme.

But I didn’t just go to the magazines for fitness or well-written essays. I also simply loved clothes, makeup, and celebrity profiles. Those fashion ads I tore out and sometimes hung on my bedroom wall? They weren’t of models with the flat stomachs or slender thighs I dreamed of, they were of gorgeous Alexander McQueen headpieces or a stunning high couture gown—pieces of art that inspired me.

Another article with scathing commentary on women’s magazines, Politico’s “The Princess Effect,” argues that whenever female political figures are profiled in the likes of Vogue or Marie Claire (the only two magazines, by the way, that the author references), they reduce them to their “supposed fashion and lifestyle choices,” decking them out in evening gowns so that we seem them smiling, packaged and sold.

I found the claim hard to believe when the article first came out last year, and I still did when I re-read it yesterday. So when I pulled out Vogue’s newest issue, which I picked up to research for this occasion, I flipped to its featured female politician: Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, France’s first female and first Muslim education minister.

Here is what the Vogue profile, titled “Tour de FORCE” (emphasis theirs, not mine), includes on Najat: a detailed and lengthy explanation of how she taught herself to become fluent in French the first year she moved the country (she was born in Morocco). Also, what inspired her to become involved in politics and how she ascended through the ranks, starting out as an advisor for the mayor of Lyon, despite a barrage a racist and sexist attacks to her character, including during her most recent handling of the country’s crisis after the Charlie Hebdo massacre. She is, throughout the profile, described as a woman with a “thirst for life” with “nerves of steel” and “a big political career ahead of her.” Every picture of her features her in the middle of work.

The profile on Najat is smart and political, but it does not represent the only way strong women should, or are, featured in these magazines. In the same issue of Vogue, cover girl Serena Williams’ hard-earned muscles are displayed in a gorgeous gown—a shoot that Williams, well known for loving fashion, no doubt appreciated. The accompanying profile then spends a large chunk of word count celebrating her female friendship with tennis rival Caroline Wozniacki.

You know who else makes an appearance in the issue? Ellen Page, discussing what fashion means to her since she has come out of the closet: “I used to feel this constant pressure to be feminine,” she admits, saying she feared people would question her sexuality before she had come out if she didn’t wear a dress. “Now I feel a sense of freedom in dressing, and I’m enjoying it so much.”

Why is it still so hard to believe that fashion can be power? In the 21st century it offers women (and men) the ability to communicate who they are and what makes them feel good. It’s, as Padukone says in her video, about “choice”—whether that choice is Page’s power suit or Rihanna’s famous sheer dress should be beside the point.

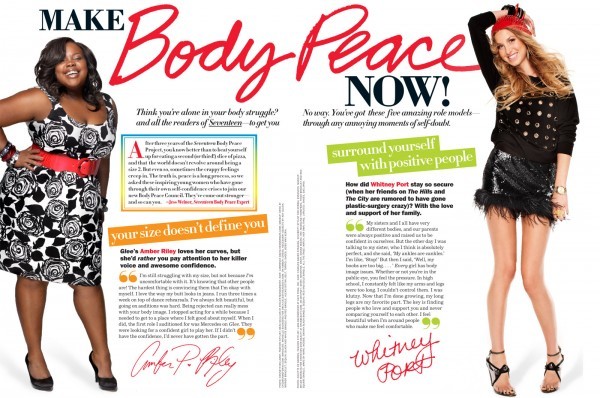

I filled three pages of notes chronicling the amazing, powerful, and independent women who were featured in this month’s Vogue, Allure, Cosmopolitan, and Seventeen while researching this article. They include, but are not limited to, Mo’ne Davis, Sheryl Sandberg, Williams, Page, a brave Cosmo beauty editor who wrote a biting and brutally honest article about her experience being diagnosed with cancer at 25, and two 16-year-old girls who created the game Tampon Wars, to fight the incredibly dumb fear that still exists regarding periods.

All strong, amazing women of different ages and occupations, of different shapes, colors sizes and sexual orientation, unafraid to go after exactly what they want in the world.

In the Quartz article, the author accuses Padukone of “vying for the spot of a confident empowered woman,” as if it’s a title that needs to be earned, as if it’s a position that necessitates checking off certain requirements and characteristics. But isn’t that taking us backwards? Putting women in boxes and labeling them because of what they wear, the way they dance, or how they put money in the bank? I learned a long time ago that “confident empowered women” come in all shapes, sizes, colors, ages, occupations, and sexual orientations. It doesn’t matter if we see them in movies, on the runway, laboratory, or Capitol Hill.

But one place I know I’ll find all of them? Featured, profiled, interviewed, and respected in the pages of my favorite magazines.

I like your analysis, but personaly nowadays I find these magazines to be to suggestive and subjective on the different ways “of being” they propose to us. I love to get a glimpse of them for the fashion trends, the good photography and some main articles, but at the end of the day, what a woman (or a man) really is can be found in their actions and work…so I always end up giving more attention to books, paintings etch.

By the way, you might find it interesting to research the history of Greece’s best women’s mag of 80-90s (i think), called “Gynaika”. It was the only one that showed a different empowered Greek woman, one that could look sexy and still write an engaging article.