Unlike the rest of Richard Linklater’s epic Boyhood, the music was added in post-production. This is an important detail. The movie is littered with cultural timestamps—video games, cell phones, politics—but it’s the music that so deliberately puts you in a time and place. So while Linklater had one shot to correctly guess which on-screen signifiers would properly capture 2004 or 2007, respectively, he was able to take a step back with regard to the music. That is, not until 2014 did he need to go back and decide which tracks resonated best with each year.

The fact that music can take us back to a moment is not a new idea. There are certain songs that remind me so vividly of a specific moment that I have a visceral reaction. I suspect most people feel something similar, even non-audiophiles. I’ll refrain from using examples because hearing about someone else’s music-based memory is a little like hearing about someone else’s dreams that don’t involve you. Music plays a part in most of our subconscious memory, but sharing that memory is generally self-promotional and obvious.

I say this as someone who both shares my experiences (often on this blog) and really fell for Boyhood. Linklater’s ability to show instead of tell, a radical departure from his oft-preachy Before series, allows Boyhood to function as an in medias res study of growing up in the aughts. Like the way music is tied to memory, boyhood (uncapitalized) is not a new phenomenon. Everyone grows up, which is true, and also something I said without any cynicism exiting the theater.

Somewhere around the one hour mark of the movie, just as we’re able to really start seeing a change in Mason’s face, I realized I should be making a mental note of these moments. As the story unfolded, I became more and more aware of the distance the movie had traveled, with each scene adding upon the last. Boyhood is a series of snapshots. Literally, in its vignette form, and figuratively in the way it lingers on moments that you don’t realize until later were “moments.” The way you’re supposed to take in the details of your own life but never do, I thought about how Mason wouldn’t remember what he was thinking riding his bike to Soulja Boy’s “Crank That,” only that that was the song playing.

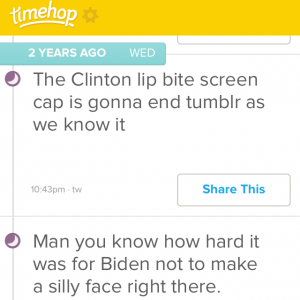

I have a love/hate relationship with Timehop, the app which compiles everything you did on social media every year on today’s date. While it can be a neat reminder of what I was thinking, its real function is to punch me in the gut with a reminder of how embarrassing I really am. I cringe at nearly every Tweet or Facebook status Timehop reminds me I posted. Nostalgia is a weird thing. We tend to think of the past hyperbolically. Something was either the best, or the worst. The majority of our lives, the innocuous moments of grey are overshadowed by large moments of extreme blacks and whites. Timehop is a sobering reminder that live-tweets from the Democratic National Convention in 2011 don’t hold up very well. My life is a compilation of days in which I said something not too interesting.

Like the film itself, the music does not have an interest in telling a specific story. We accept the passage of time as sufficient narration, and in the same way, music, both the diegetic and non-diegetic, operate in a straight-forward way. But like how Timehop reminds me that I am incredibly corny most of the time, Boyhood does not edit Mason’s music taste. It’s authentic and perfect in the way only something so embarrassing can be. You like to think of your younger self as someone who was with it, but the truth is that every trend that has since passed and turned into a Buzzfeed Rewind post was actually something you whole-heartedly cared about.

I admittedly care way too much about what is cool. And as a result, I would never ever be able to watch a Boyhood-style movie about myself. I can’t even stand my tweets from yesterday. I thought about my little brother a lot during Boyhood. I’ve always seen my role as an older sibling as someone who should try to mitigate my little brother’s current embarrassments for the sake of his future self. My thought process was that I wished an older sibling had told me not to record myself playing acoustic guitar, etc. Though my intentions were good, Boyhood serves as a reminder that it’s precisely all the stupid, embarrassing, what-was-I-thinking moments that create a whole human being.

The music in Boyhood is simply what the characters were listening to at the time, presented without comment. Some of it is great and iconic, some of it is bad and clearly of a different era. In a film that relies so much on life stages, the ability of the soundtrack to take us to that time in a way that doesn’t feel forced is impressive. Over time, our interests change—I’m sure Mason wouldn’t want to admit he was really into “Let It Die” by the Foo Fighters but maybe that’s just me projecting because I was really into that song when I was 17, but would never want anyone to know that. Ultimately, we are all an embarrassment.